Merriam-Webster defines sin in three ways—“as an offense against religious or moral law; an action that is or is felt to be highly reprehensible; or a serious shortcoming or fault.” On the dark side of global philanthropy, bad things do happen. The accumulation of wealth and advanced educational degrees does not always equal understanding of how to respectfully support social change in communities.

Whether these transgressions rise to the level of an offense against religious law is a debate best left to theologians. However, examining the worst sins of the philanthropic sector and possible ways to remediate these issues occupies the thoughts of many of those active in the foundation world.

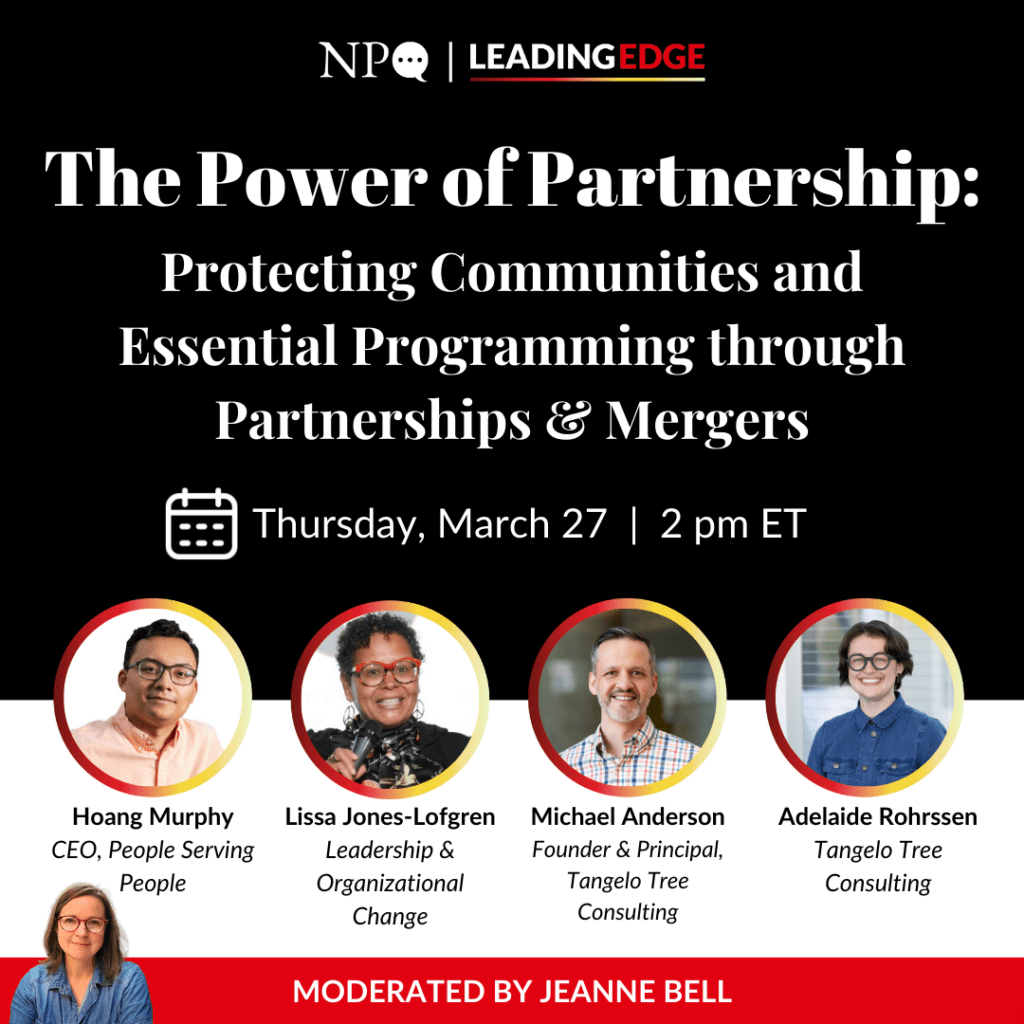

From a survey I conducted of senior philanthropic leaders across all type of foundations—from the small and local to the large and global—I derived this list of the top seven deadly philanthropic sins.

- Blindness to privilege

- Dismissing community knowledge

- Misplaced accountability

- Poor partners

- Failure to learn

- Risk aversion

- Lack of transparency

Blindness to Privilege

According to a 2015 study by the Council of Foundations, some 75 percent of full-time paid foundation staff in the United States identify as white. Any discussion of privilege and power in the sector must also focus on the impact of white privilege in philanthropic giving.

“Most people that are in leadership have had a very similar life path. They have been taught that the rigor comes from researchers in a dominant cultural model that’s university based and uses very Western ideas and intelligence,” says Kara Inae Carlisle, vice president of programs at the McKnight Foundation. Loren Harris of the Nathan Cummings Foundations calls it a “knowledge hierarchy” where community knowledge is sometimes valued near the bottom. He contends that valuing some knowledges over others leads to a lack of faith in community understanding of a problem.

Carlisle observes that, “There are increasingly few places in the country where there’s not going to be significant racial and cultural differences…where people who have been very sheltered or in dominant culture settings are beginning to say, ‘Wow, we are fish in water. We didn’t know we were fish. We didn’t know we were swimming in water.’”

Don Chen, Director of the Equitable Development Team at the Ford Foundation, remarks that he wishes he “had a dollar for every organization that comes to me and says our board came up with a new strategic plan, and we are going to focus on equity. These same people aren’t talking about equity as a core value or a core component of their mission; they are often talking about equity as a topic. That’s a warning sign for me because it could be dropped like any other topic.”

“We have to always remember that we are operating within the public trust and with that comes profound responsibility,” says Harris. He said that, as sector, we are still not dealing with gender equality and racial injustice because many organizations are still funded, year after year without any real change in how they operate.

“We are complicit in maintaining the structural inequality” built into capitalism, says Harris. “Why don’t we use our privilege and power to hold people accountable to spend more of their giant endowments?” Most philanthropic dollars make returns of seven to 10 percent, while foundations typically spent only four to five percent of their return as required by their tax status.

Harris adds that, “We are largely silent where we could be vocal, and we are largely inactive where we could be proactive. And those are sins of greed and gluttony and wanting to have assets that grow and grow and grow.” Harris also poses a provocative question to the sector: “Are we just going to be a release valves to the social pressure on capitalism? Or we could actually try to transform capitalism?”

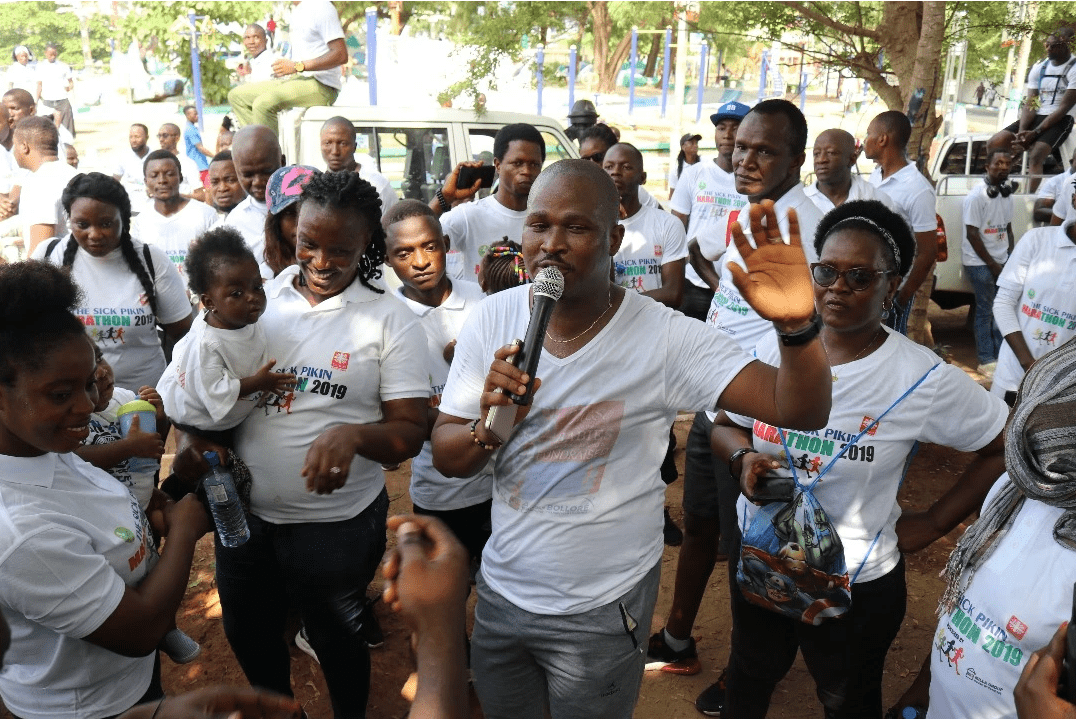

Dismissing Community Knowledge

An antidote for privilege and the power imbalance, according to Diana Sieger, CEO of the Grand Rapids Community Foundation, “is taking the time to listen for the possibilities and then adapt to community knowledge,” instead of shutting down grant-seekers because their ideas “are just too much work.” Harris agrees that the simple fix is “listening better, engaging better, and engagement in community knowledge.”

But this is often not done. Fred Keller is retired now, but formerly served as chair and long-time trustee of the W.K. Kellogg Foundation. Keller observes that too often, “we ride into communities, stand before them, and tell them what they need to do to solve their problems. Then we ride out, expecting programs to be scaled and sustained.”

“Foundation people tend to over-intellectualize but under-experience the challenges of those they seek to serve with no authentic proximity to the issues,” says Carlisle. She continued, “The validity that comes with seeing and understanding different world views, which are not dominant culture, can have extraordinary outcomes.”

“Many in the field prioritize communities being able to shape their own destinies and direction.” Embedded in failure is “the lack of focus on empowering communities to solve problems on their own, especially if foundations aren’t going to stick around forever,” says Chen. Chen calls it “drive-by grantmaking,” where foundations make a grant and then go away for a year or two. “Local folks have a BS meter and they know if you don’t trust their knowledge,” says Harris.

“We need to realize that grantees come to the table with knowledge and passion. We could save them so much time and energy by not holding them accountable to reports that nobody reads,” says Carlisle. She suggested philanthropy might focus more on the community context, high trust, and quality of relationships that are less about control and more collectivist, a non-dominant cultural model.

Harris sees that this lack of trust leads to “so much vetting and so much paperwork when bad apples are the minority.” He adds, “How can you understand community needs when you don’t really trust the community to even articulate their needs themselves? And you don’t trust their understanding of their community needs themselves.”

Foundations don’t know everything and neither do communities. For these relationships to work, “Communities have to trust that what you’re bringing to them is coming from a genuine desire to improve their lives. And you have to trust that when they say, ‘No, we don’t want that,’ that’s a good decision. They thought about it, they’ve heard you out, they learned about what you want to introduce to them, and now it’s time to do what they asked for,” says Harris.

Misplaced Accountability

At its core, philanthropy is a very privileged sector. Said one survey respondent, “Most CEOs are trying to impress a group of usually very highly privileged board members, and what falls by the wayside are the people that we should be most accountable to—those living with such disparities as access to asset building, jobs, safe neighborhoods, quality education, healthcare, legal rights, and civil rights.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

According to Chen, one example of this is the tendency in the field “to go where a lot of others are going, and not rely on experience and all the evidence we have around us. We don’t often enough think and re-think about how to do the best work, but we go along with what is hot.”

Poor Partners

Collaborations, concludes the MacArthur Foundation, can have significant benefits: larger pools of financial resources; mitigating donor risk; helping enter new policy or geographic areas; drawing attention to issues or places or organizations; and shaping policy agendas.

Why, then, is collaboration so hard? Several interviewees discussed the difficulty that foundations have collaborating with one another. “Lack of coordination among philanthropies is huge,” said one respondent. “I hope that philanthropy can learn how to partner and be better strategic allies to one another to move change.”

Failure to Learn

“Failure is just information,” says Sieger, while Harris contends that many in philanthropy want to be learners in learning organizations but don’t know how: “We are ashamed of failure, and it connects to such a powerful emotion. Instead, we need to create space where people can lean into setbacks and failures.”

Neal Hegarty, Vice President of Programs at the Mott Foundation, says, “In philanthropy, we don’t always clean up our messes when we change priorities and make transitions.” Hegarty offers that the unwillingness to learn may stem from “a tendency to think we are the smartest persons in the room and the assumption that we have all answers and understand all the angles.” That fundamental arrogance or lack of humility is a significant barrier to admitting failure and being willing to learn from mistakes, or what Hegarty calls “faux humility.” Failure is just a new opportunity as long as it is viewed without “rose-colored glasses,” Hegarty says.

Another possibility that Chen offers is that the field is “delusional” about what was or could be accomplished with the amount of money offered. Sometimes, Chen said, the sector believes it is “smarter than everyone who ever came before. Especially when working in in under-resourced, low-capacity places, philanthropy tends to think it has super powers.”

Then, as a program officer at another national foundation adds, we get moved by the “flavor of the month.”

“We ask a lot of our grantees and then what they share with us goes into a black hole. We never do anything with the information to further the work,” said the officer. “Without processing the information and developing a vehicle to get it back to the grantees, much learning is lost.”

Risk Aversion

Foundations that are only accountable to their donors and their boards are well suited to take on high-risk experiments democracies need. The lived experience for many in the sector can be the opposite, however.

“There is not the opportunity to be as creative or to be a risk-taker, because if it doesn’t work out, it may hurt my career and I fear repercussions,” said one respondent. “That means, we make safe bets and bet on safe organizations,” she said. Harris suggests, “It’s about understanding and having a language for and tools for risk.”

Hegarty said he cringes when he hears foundation people talking about risk. “The journalists and activists who put their lives on the line in the pursuit of openness and freedom, that’s risk. Philanthropy certainly risks financial capital, but we need to be cognizant that the term ‘risk’ takes a much different meaning for many in the fields we support.”

Lack of Transparency

Foundations have no legal requirement to share information except for annually filing the IRS’ 990 form. They aren’t required by law to even report how they use their funds.

“So much of what we fund is designed to create a better way of doing things, whether it is new models or how we reach a certain population, or a better way to get the public sector to work together,” says Chen. Foundations often do come up with better models or ways of working but “fall down on having something to show for it.” Chen says, “If we are honest about it, we should be transparent about how we are measuring it [change] and then what the results are.”

Chen says the sector has a long way to go. “We can be much more transparent about our values, about how we work, about how we make decisions, about what impact really means.” He thinks the sector doesn’t have a lot of answers and needs to be clear about that with partners and grantees.

Go forth and sin no more…

To combat these issues, Chen says he looks for people who are experienced and who aren’t pompous or into “magical thinking.” He also noted the tendency of some foundations to avoid conflict. “We’ve tried very hard to address our culture of deference that…makes for a very nice work environment but…means people aren’t asking each other legitimate questions about their work to improve it.”

Another respondent from a small family foundation says the biggest challenge is when foundations insist on setting the outcome for change work, “confusing our vision with local outcomes.” As Kate Markel of the McGregor Fund notes, “Foundations don’t do the work themselves and they don’t control the outcomes.”

As a sector, philanthropy has to struggle against its desire to be “popular and to be liked,” says one respondent. “There will be people who don’t like us, and we have to have thicker skins and be able to stand in our own truth about who we are as an organization because that can inhibit us for moving real change,” adds another interviewee.

Harris sees these sins in the larger national context. “At the heart of this is what is wrong with our democracy—misinformation, outright lies, and the apathy that comes from people losing faith our institutions.” Philanthropy has played a part in the loss of faith in institutions. The solution, Harris suggests, is for “philanthropy to be more transparent, more engaged and proactively forthcoming when it comes to power we wield and the privilege that conceals our shortcomings.”